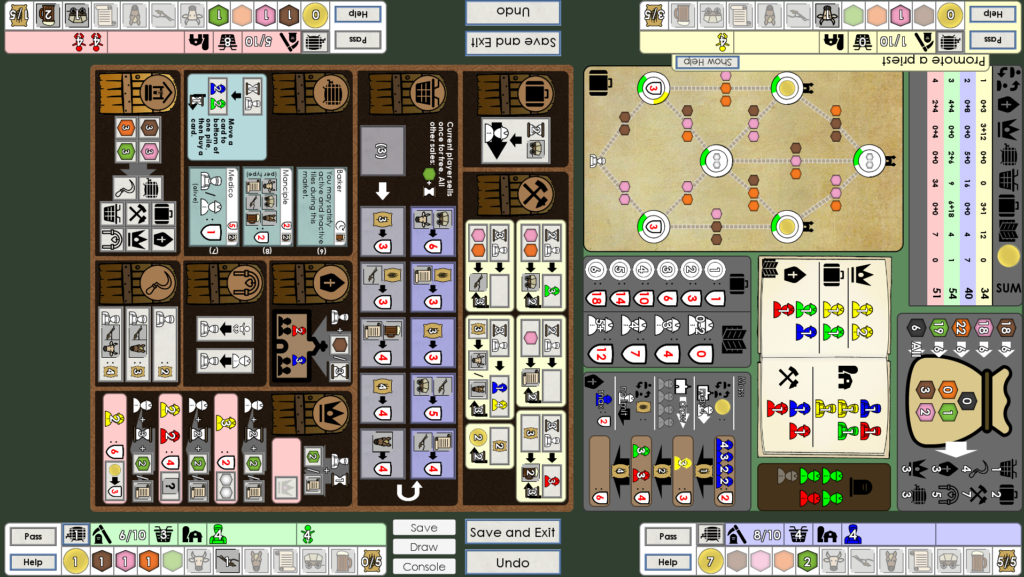

I’ve completed a touch-table version of the board game Village.

Village has an interesting mechanic where you manage the life and death of your workers. All your workers start as farmers and can be trained as specialists. Actions take “time” to perform, and when enough “time” has passed, a worker dies. A limited number of each type of worker is rewarded with fame and victory points upon death while the rest get an anonymous grave. The key is making the best use of your workers and their time while trying to arrange a good death.

Village has an interesting mechanic where you manage the life and death of your workers. All your workers start as farmers and can be trained as specialists. Actions take “time” to perform, and when enough “time” has passed, a worker dies. A limited number of each type of worker is rewarded with fame and victory points upon death while the rest get an anonymous grave. The key is making the best use of your workers and their time while trying to arrange a good death.

This game was similar in size to Age of Discovery. There were two parts of this project that were time consuming. The first was just the number of different actions that a player can take on their turn. There were just lots of (relatively easy) cases to implement. The second difficulty was for the “Inn” expansion. That expansion added a lot of unique cards to the game that the players can buy and use. Each card needed to be coded. So again, a lot of fairly simple cases to implement.

I was able to re-use all the standard code, along with my map code from Concordia.

As you can see, the screen is pretty full. The game takes up a lot of room on the table too. It felt like I spent more time than average laying out the graphics for this game. Honestly though, it always takes a long time to do the graphics for a game. It used to be something that I really disliked, but as I get used to Photoshop and Unity, I’m enjoying it more. Now my least favorite part of the game is audio and animations.

Game state

I used our standard event system to perform the actions in this game. The event system is great, but doesn’t really help with managing game state.

In most games I have an enumeration of game states, and data about the state of the game is stored in either the player or game class. This works well for games with relatively simple state. After doing Age of Discovery, I knew that it would have been better to have a full state machine or at least a set of state classes. I haven’t done that for any of my games, so I decided to try it out for this one.

I didn’t make a full state machine, but I did make a set of classes to store what state the game is in and any data that I need about that state. When I had an enumeration, it was easy to check what state the game was it. I had lots of code that looked like:

if ( Game.theGame.CurrentState == Game.StateType.PickAction &&

Game.theGame.ActionArea == Game.ActionType.Travel)

Now that I was keeping a stack of classes to represent the state, I was going to have code that looked like

if ( Game.theGame.StateStack.Count > 0 && Game.theGame.StateStack[0] is GS_PickAction &&

(Game.theGame.StateStack[0] as GS_PickAction).ActionArea == GS_PickAction.ActionType.Travel )

That may not look like a big difference, but I ended up writing a line of code similar to that 125 times in this project. So to save some typing, I added some templated convenience functions and ended up with if checks that looked like:

if ( Game.theGame.isCurrentState<GS_PickAction() &&

Game.theGame.CurrentState<GS_PickAction>().ActionArea == GS_PickAction.ActionType.Travel )

I think that having state classes is probably a good idea. It keeps the model code cleaner since I don’t have to keep adding member variables for storing state details.

For Village, I made events that were not state dependent but were instead action dependent. So instead of having an event for picking a worker to kill, picking a worker to train, and picking a worker to activate, I had one event called PSelectWorker that then checked the state of the game and did different things.

Unfortunately, that made my events grow larger and larger as I added each part of the game. The event classes ended up being too complex and difficult to maintain. Instead, I should have put a lot of the event functionality into the state classes. So I’d still have a PSelectWorker event, but the event would then ask the current state to handle the selection of a worker.

Next game I will try this method.

Hours and Lines of Code

At 85 hours, Village is a standard “large” project. This is probably my favorite length for a project. It is long enough to feel like a big game and have interesting challenges, but not big enough so that I start forgetting how I implemented things in the middle of the project.

I was able to reuse some art assets from other games and the rest of the assets were fairly easy to find. As usual, I used thenounproject for most of the art and Unity assets for the audio.

| Task | Time | Percent | Percent in Age of Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asset creation | 7 hr | 8% | 12% |

| GUI layout | 28 hr | 32% | 24% |

| Coding | 39 hr | 45% | 44% |

| Testing | 13 hr | 15% | 20% |

To get an estimate for the lines of code created by Unity for GUI layout, I estimated that each hour of coding created 87 lines of new code. At that rate, the time I spent on the GUI would be 2443 lines of code. So the GUI layout and Coding tasks are further broken down by what type of code they create:

| Task | Lines | Percent | Percent in Age of Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| GUI layout | 2443 | 42% | 33% |

| Graphics/Animation | 1444 | 25% | 24% |

| Game model | 789 | 13% | 13% |

| Game flow | 820 | 14% | 25% |

| Full reuse | 247 | 4% | 4% |

| Partial reuse | 104 | 2% | 1% |

At 5847 lines of code and 85 hours, this project was very similar in size to Age of Discovery. That makes it a large game – maybe a bit larger than I expected it to be. But not nearly as large as a very complex game like Caverna or Terra Mystica.

It is also really nice to be able to re-use so much from other projects. I started the GUI for this project by copying the layout from Age of Discovery. This gave me a lot of the main menu, camera, canvases and controller setup for free. But I did have to spend a bit of time cleaning up the rest of the GUI.

One thought on “Touch table Village”